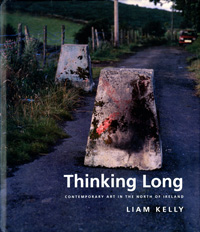

Excerpt from Thinking Long: Contemporary Art in the North of Ireland by Liam Kelly, pp. 40-42. Published by Gandon Editions, 1996.

John Carson has always been uncomfortable about the peripheral nature of much gallery-based fine art practice affording little access to non-initiates. The body of work he has produced since leaving college has therefore been an attempt to bridge the gap between the private and the popular audience. His modus operandi has consequently been an interactive use of humor, dry wit and irony: playbacks to an audience who best know themselves but need reminding.

To this extent he has deployed a wide range of media, including photography, posters, postcards, video, television, and live performance. Work in this category has included storytelling with slide presentation, as in Off Pat (1985-87) and So What (1990). They present the absurdity in the everyday little events of the human condition – contradictions in response to a regional accent, the shenanigans of the local hard man, Billy Liar-like private fantasies of fame. These are very entertaining and droll but are they art? A question often asked of this aspect of Carson’s work. Noel Sheridan seems to think it resides in the space between language and image:

There is an amount of slippage between the narrative and the images and it is the tension and humour generated by conceptually trying to bridge these gaps that surfaces the art analysis and the politics within the work.

Carson himself sees his work like gathering and presenting evidence – not totally disinterested, he puts emphasis here and there – but the audience will make up his own mind. This offering up of evidence has resulted in a serial presentation of images in the artist’s work. Different locations, too, are important as they bring unpredictable interactions. In the past, he admired the work of Richard Long and Irish artists Brian King’s interventions with nature, and, while at college, he rejected making art objects for making art journeys. Friends, Walks, Hills, Invisible Lines and Belfast Lough (1976-77) is a triangular journey, crossing divides, around the area of his childhood: a cultural embrace.

In 1978, Carson produced two time-based photoworks – A Bottle Of Stout In Every Pub In Buncrana and I’d Walk from Cork To Larne To See the Forty Shades of Green – both turning romantic and stereotypical images of Ireland into lived experience. In the nineteenth pub of his twenty-two-pub crawl, Carson was almost refused a drink. The situation rescued, the young artists completed the course – dead drunk. Buncrana is not untypical of some Irish towns where it seems every other house is a public house. The ritualized cycle of drinking on Irish terrestrial walkabout contrasts markedly with the Sistine Chapel ceiling, where Noah’s condition is noted above, on entrance, and the journey is towards spiritual dying out, at the altar end. Seeking sponsorship from Guinness for his project poster, Carson was forced to explain his intentions:

In ritualizing the drinking situation and pointing out the effect of too much alcohol and in depicting all the different types of pub in Buncrana, my intention is to get people to focus in on and take a considered look at our traditional Irish drinking habits. It is then up to the viewer of the work to wonder whether the drinking habit is a valuable cultural heritage, a desirable social activity, a futile indulgence, a sinful business or a serious matter for concern.

Guinness were not amused. ‘We, as a company, are concerned with moderation and your proposal would not be in keeping with this approach.’ Carson saw it as a real hypocrisy, considering how they made their fortune.

The Forty Shades of Green (1978) depicted a 320-mile journey, taking the ‘unexperienced’ romantic illusion of the Johnny Cash song and recording the reality – green soldiers’ uniform, green milk crates, and the ‘go’ sign of traffic lights. The colourblindness of the song was deconstructed, the ‘on the road’ experience offering a more mundane experience.

To complete this trilogy of debunking cultural production, Carson went on the road again, this time to America and by car. In American Medley (1981-84), he visited towns as place-names in songs, such as ‘Twenty Four Hours from Tulsa’ and ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix’. In Clarksville, Carson spent the morning looking for the train station, mentioned in the song, only to find Clarksville has no station. The seduction of ‘otherness’, offered in this litany of exciting place-names, resides in our desire for discovery. And the American pop song is a perfect example of how America has colonized our consciousness. Unlike other performance artists who use ritual as a primitive, animistic force, Carson, in American Medley, uses it in an existential mode to reflect the culture to itself. Joan Fowler explains his use of ritual:

Carson’s interests are therefore in the only kind of ritual which is common to all western culture – and which isn’t self-conscious or enforced ritual, a contradiction in terms – and in these respects he has used the rituals of pop music as a critique of a particular society which is in the realm of myth within our own.