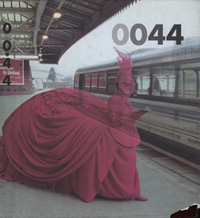

Laughter in the White Cube by Mic Moroney from 0044 – Irish Artists in Britain, pp.32-39. Published by Gandon Editions, 1999.

Considering a lot of John Carson’s work, it’s almost no accident that the town he hails from on the northern shore of Belfast Lough in Northern Ireland is commemorated by an old emigration song, probably more famous than the town itself, ‘I wish I was in Carrickfergus’, although, as Carson often remarks, ‘I can think of at least 5,000 people who wish they weren’t in Carrickfergus.’

Now 47, and living in London since 1984 with Mary-Lou and their kids Frank and Rose, Carson has never lost that strong Carrickfergus accent nor, with it, the deeply skeptical mindset and flattening, black Northern absurdism. With Carson, it comes across as a kind of forlorn, self-deprecatory, lop-sided comedy which pervades his deadpan performances.

It is also there somewhere in his many documentary works. His new wall-piece for this show germinated over the past year whilst Carson made his daily way across the ethnic clutter and street furniture of London. Again and again, his eye was caught by the ubiquitous, immigrant family-business Turkish and Greek kebab shops, and with them the emergence of what Carson sees as an international graphic icon of the doner kebab meat-block. Lumpen but unmistakable on its vertical skewer, it is as universal as recognizable, in Carson’s words, ‘as the cross, the swastika or the shamrock’.

It’s an old strategy of Carson’s: a serial documentary of an object or idea, absurdly threaded together into a bumpy narrative, or, as here, a repeating pattern across a grid of photographs. In each, the kebab sign has been excised and whited out, like the silhouette of an absent person, a mysterious icon. Yet, for all the idiosyncratic variation, its shape gives it away instantly, with Carson making a pictogrammatic, almost hieroglyphical statement from something invisibly commonplace, marginalized, yet carrying enormous currency in London and other European cities.

An analogous and very successful documentary work a couple of years ago was his Evening Echoes (in collaboration with composer Conor Kelly), which paid warm tribute to the almost mediaeval figure of the street newspaper-seller. Typically, the piece involved travelling to twenty-three towns and cities throughout England, Scotland, and Ireland (Dublin and Cork in the Republic, Belfast in the North) and, after the Cornerhouse in Manchester, the resulting exhibition toured similar terrain.

Carson’s black and white photographs of the vendors, both men and women, and the spaces they marked out for their stalls on the street, were mounted almost life-size, accompanied by Kelly’s recordings of their wild, often incomprehensible cries hawking the Chronicles and Stars; phrases like ‘All tomorrow’s winners, all tonight’s telly’, worn smooth by melody and repetition. All this, embedded in the surf of traffic and street sounds – high-heeled shoes, conversation, car alarms, gulls, and other busking street music.

If such ‘conceptual’ art is often dismissed as ‘pointing at things’, Carson simply magnified something invisible and human in the urban texture, bringing the street indoors and making the vendors themselves news, in a way, like a threatened species in the commercial walking streets of British and Irish town centres. And as ever, there’s an autobiographical strand – Carson’s childhood memories of shopping trips to Belfast with his father, and his alarm at the old-timer selling the Telegraph breaking into the baffling yodel of ‘Telay-olay’.

Art-wise, Carson’s inspirational roots come from the era of Richard Long and his ritual documentation of journeys and landscapes. Although Carson originally studied architecture in Nottingham, he returned in the mid-seventies to study fine art at the Ulster Polytechnic in Belfast – then and since, a horizon city of the North from which college kids normally evaporate away to other climes.

But Carson stayed on for three more years, working full-time on the pilot boats which guided the diminishing freight traffic into Belfast Lough. (His father had worked the shipyards all his life.) As always, Carson documented his environment – the men-only working culture of the seafarers – with a notice board cluttered with photographs, news clippings and topless page-three girls. (The work became part of a show, Art & the Sea, which toured Britain in the early 1980s.) It was only then that he left to do his post-grad at the California Institute of the Arts with his then idols, the laid-back early conceptualists, John Baldessari and Douglas Heubler.

One early piece after college in Belfast in the late 1970s was a large-format booklet which documented networks of friendships, walks, and ‘actions’, which pointed slicedly across the deeply sectarian mosaic of the Belfast area. Hilltop Line, for example, involved Carson and four other guys climbing to the tops of hills around Belfast Lough, from Black Mountain, over west Belfast, to Whap’s Hill outside Carrickfergus. Armed with large mirrors, they relayed flashed signals of reflected sunlight according to a prearranged timetable – a druidically daft gesture which, considering the military and paramilitary tensions in the area at the time, could easily have resulted in a good questioning.

‘I was stopped by “security forces” a few times while doing these outdoor projects,” recalls Carson. ‘I remember one time – it was about three or four in the morning – I had walked twenty-five miles around the edge of Belfast Lough and then rowed seven miles across a rough current from Bangor to Whitehead. I was wearily shuffling the five-mile road back to Carrickfergus when I was pulled over by a UDR patrol. On my back, I had a rucksack which contained the last stone from a set of twenty-four which I had been depositing and photographing at various intervals along the route. The UDR man asked me what was in the rucksack, and I told him it was just a stone. But he insisted I showed him. Then he asked what I was going to do with it. And I had to tell him I was taking it home to bury it in the garden. As you can imagine, there was some discussion on the topic in the back of the Land Rover, before I was sent on my way.’

Another early piece, which Carson toured widely as a performance, was Men of Ireland, with Carson costumed-mimicking nine wooden cut-outs of stereotypical Irishmen – a clergyman, a workman, an Orangeman, a leprechaun with a shillelagh (Carson himself is only 5’3” tall), even a paramilitary. With Carson outfitted in shades and hooded anorak, and wielding a baseball bat, this last incarnation cowed viewers outside Northern Ireland into appalled silence, while Belfast audiences invariably burst out laughing.

Apart from nosing out the perversities of the Troubles, Carson’s other earlier Irish work assailed romantic and mythic theme-park notions of Ireland. One piece, A bottle of stout in every pub in Buncrana, pointed up the old, tragic, Irish joke of the drink. The title says it all – the pint-sized Carson weaving his way through the twenty-two hostelries of that godly little Donegal town. Apart from one gastric heave-ho, the resultant booklet documents Carson’s worsening condition, as well as (gleefully) his correspondence with Guinness in the vain hopes of sponsorship – the company found Carson’s performance out of kilter with its own supposed marketing message of ‘moderation’.

Another old satiric piece, 40 shades of green, was grounded in the famous Johnny Cash song, and involved walking the 320 miles from Cork to Larne across the surreal partition of the border. Along the way, Carson photographed anything green – cabbages, milk-crates, ‘go’ signs, industrial complexes, railings, somebody’s plastic coat, grassy dereliction, military camouflage fatigues above a British soldier’s boots. The forty photographs of his poster radically deconstructed the song’s dewy-eyed sentiments.

Later, driving across the US to fifty cities famed in song, and collecting postcards and taking polaroids as he went, Carson created his American Medley, which saw life variously as performance, video and even a photowork festooned around an old jukebox in an American-style restaurant in Belfast.

In performance, Carson, standing in front of projected slides of the images in gaudy tourist garb, relentlessly bludgeoning the familiar tunes (‘By the time I get to Phoenix’, ‘Twenty four hours from Tulsa’, etc) into his naked vernacular – a bemused celebration of US cultural imperialism, illustrated by his gritty or poignant polaroids which jarred with the sunlit, colour-saturated scenes of the postcards. ‘I remember walking around the streets of Clarkesville, asking people the way to the railway station mentioned in the song, and everyone I asked looked at me as if I was slightly crazy. Eventually someone was good enough to reply, “there ain’t no railroad station in Clarkesville”.’

Story and song is a very Irish thing of course, from the days before TV when ‘you made your own entertainment’. Carson’s house was always full of song, although, coming from a Presbyterian, and, indeed, loyalist background, he came into contact with little of the sean nos, or old style traditional singing in Irish. Rather, the songs which pervaded the house were popular recorded songs and music-hall numbers – very much the starting point for Carson’s heartfelt, slightly off-pitch sing of that kind that most people reserve for the shower. ‘Someone once asked me how did I remember the words of all those old songs. But how do you forget them?’

Comedy, both intended and willfully inadvertent, was always at the core of Carson’s main travelling performance piece, called variously Off Pat or So What or even An Evening with John Carson. Snapping from singing in the hoarse, high voice to disjointed, desultory storytelling, from the random redundancies of Carrickfergus banter to mundane first-person incidents, Carson delivered his confessions like an eccentric TV anchorman, beneath a series of apparently unrelated slide projections – a kind of sit-down comedy device his fellow Northerner, comedian Kevin McAleer, later became well known for.

One of his many surreal juxtapositions was a slide of the veteran Free Presbyterian leader and fomenter of Ulster’s Democratic Unionist Party, Ian Paisley, with the word ‘PADDY’ plastered across him. Carson usually accompanied this with a commentary of how, having come from good loyalist stock, his own inescapable Irishness was starkly brought home to him in London, where he was roughed up in bars on more than one occasion for having the accent of an IRA man.

In a sense, Carson is a misfit in any medium, even the art world where he ploughs his own eccentric, yet curiously populist furrow. Even when he clowns, as in Head Honcho, a video for the BBC (a comic portrait of a hard man who headbutts everything from a corrugated iron gate to his own mirror image), Carson gives a look to the camera which eschews the mechanics of comedy, as if there’s a catch – that he’s desperately abusing the conventions, or even that he’s taking the piss out of himself. (I never got to hear tapes of his radio project in Liverpool, The Wee Johnny Carson Show, with no guests over 5’3”.)

Carson: ‘Certainly, in the art game, I have never stayed dedicated to anything. I never stuck to being a performance artist or a photographer or a video artist, so I have never really felt affiliated. If somebody comes towards me with a label, I find myself backing off, or dodging.’ But Carson has a knack for pointing up alienation and absurdity. Rifling through his material, I was very taken by one bemused text/image piece after a residency in ‘Planet Perth’ in Australia. Over the world ‘Dreamtime’ he selected two photographic images, one a petrified tree, quickly evoking aboriginal realities, the other, a skyscraper halted in mid-construction due to a collapse in the white man’s building boom. Elsewhere, a text: ‘That’s the difference between them and us’, illustrated by the Australian version of Marmite called Vegemite, and a photo of the oddly shaped three-pin Australian plugs. A neat enough commentary on global urbanity,

Carson is also a ready collaborator and organizer. While in Dublin, he ran the gallery in the old Grapevine Arts Center, and he clicked into London through his work as curator/project manager with Roger Took’s Artangel Trust, working on his big public projects with artists like Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, and Krzysztof Wodiczko. He is now a full-time lecturer at Central Saint Martin’s College in London, where he also makes the crucial links for students wishing to do public projects.

One recent video collaboration of his own, You Don’t Say, was a nine-minute video made for the BBC with Scottish performer Donna Rutherford and director Deborah May. ‘It’s my first adult video,’ says Carson. ‘It’s got a shower scene and a bed scene and a fight scene. It was meant to be about miscommunication between men and women, but I think it comes across as being about the impossibility of a perfect relationship. I wanted it to be intense and serious, and there’s pathos in there as well, but the comedy sneaked in again. Of course I’m serious about my art, but coming from the background that I do, it’s hard not to find art-making a fundamentally absurd activity, and I can never help seeing a daft side of things.’

Carson’s other pieces in this 0044 show come from a peculiar, almost cheerfully rueful show last year called Days, in the little Central Point Gallery around the corner from Central Saint Martin’s. Unusually for Carson, these are abstracts, but of course, there’s a yarn behind them. The large laser-copied banners are enormous blow-ups of pages from his colourfully untidy professional diaries over his seven years at the college. Planned meetings or calls, if achieved, are erased beneath a graffitoid, felt-tip doodle which Carson magnifies into a kind of accidental expressionism, a glorified detritus, a toejam of years.

It struck me that the blank of leaf-litter of Days contrasted sharply with Carson’s strong sense of nostalgia for Ireland, north and south. London, he said, was ‘only the place I happen to be’, and he missed the ‘craic’ back in Ireland, the singing and music, particularly. Invited in 1994 to do a window piece for the new Irish Centre in Hammersmith, he readily etched white outlines of all thirty-two counties of Ireland (an odd statement from a Protestant-stock Ulsterman), all floating free of each other and largely unrecognizable. With each, a line or phrase from a song of that county: ‘at every corner, a hearty welcome’ or ‘woodbines in full bloom’.

Carson: ‘I think of it as a silent songwork. I like the idea of Irish exiles standing in front of it with all the songs going around in their heads, as opposed to passing Londoners who can only be baffled, because to them it’s back-to-front nonsense. It’s probably the only deliberately “exclusive” work I’ve ever done.’

Carson goes back a couple of times a year to Carrickfergus, which he still refers to as his ‘reality gauge’, yet which is ‘both a home and not a home’. Now a predominantly Protestant dormitory town of Belfast, with small new vulnerable pockets of Catholics, it’s no longer the family home either. Carson’s sisters have long moved out, and the greatest link was severed when his mother died three years ago.

Recently, he went back to the old house and removed a few boxloads of childhood and teenage memorabilia of family life – material he wishes to make something from, but it’s a project that will take time. Meanwhile, the boxes remain, awaiting the full archival treatment in his ‘studio’ – a slope-floored office which betrays an alarming sense of quixotic order.

In response to my questions, he was able to quickly pull files from the shelves – work and related documentation spanning two decades, catalogues, personal and professional correspondence, polaroids and other photographs, like the one he showed me of a friend who had since died in a car crash – the raw materials of an imagination played out in the enormous shadow of memory.